"Aerated concrete is only one of the problems" - Cheney Payne

I will be returning to school for my twelfth year as a teacher in September. While every school year presents new challenges, the "aerated concrete" scandal is a new low for this government, throwing schools and families into complete confusion about whether their school is safe, and whether their children can go back into the classroom today. At the beginning of a school year, there is always plenty to do and plenty for our children to be worried about. Not only is this a disaster, but it's a really badly timed one for children who already find the return to school challenging.

This is not the first example of the Conservatives' mismanagement of our education system, and I'm sure it won't be the last. However, dramatic as it may seem, it is arguably not the biggest challenge schools will face this year.

The news headlines rarely begin to scrape beneath the surface of the huge difficulties our young people have faced returning to school since the pandemic. Geoff Barton, General Secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, wrote a few months ago about how the experience of working in a school has changed fundamentally since the pandemic, with school leaders across the country highlighting behaviour, social media and mental health as prime factors leading to the day in, day out experience in schools becoming more and more difficult. Our students are struggling. Perhaps unsurprisingly, yanking young people in and out of the structures and social lives they know with no time for preparation, and confused messaging from their government about who should be isolating and when, isn’t easy during one’s formative years. I doubt that being told your classroom could fall down is any more reassuring.

As a teacher and the candidate to be your MP, education is my top priority. Therefore, as schools return this week, I wanted to share my thoughts on the real issues in education at the moment, and what we should be doing about it.

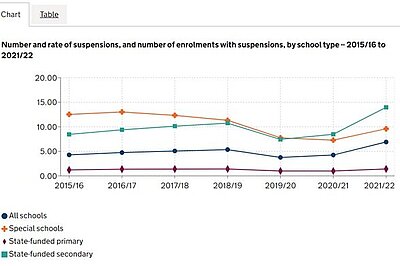

School suspension rates are at an all time high.

When the government published the data on permanent exclusion and suspensions in July this year, they showed the highest figures for the last 20 years. Across all types of schools, suspension levels increased significantly from 2018/2019, the last full academic year students spent in school before the pandemic to 2021: by 68% for secondary school students and 43% for primary school students.

After months of lockdown learning, our young people are finding it incredibly difficult to adapt to the structure, routines and consistency of a school day, and more than ever before are finding this impossible. Anyone working in a school or with children going to school will be able to give examples of this: but the government is simply not talking about it.

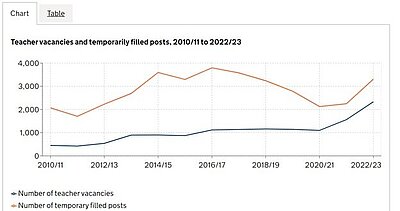

Teacher recruitment is in crisis.

As schools prepare to open their doors to the students again next week, many will do so with vacancies for classroom teachers, and temporary supply agencies being used to fill these gaps. The Department for Education reported in June that teacher vacancies have doubled in the last two years, with 3000 posts now filled with temporary supply agencies rather than permanent teachers. There aren’t enough people wanting to enter the profession to give our students the experience they deserve. Fewer teachers means more pressure on those still working, creating a vicious cycle that the government has utterly failed to address.

Some schools are chronically under-funded.

While Cambridgeshire schools received a funding uplift in 2022-2023, this does not balance out years of under-funding under the National Funding Formula. The County Council is left with a £40 million gap in its “high needs block”: this is the area of funding which supports students with Special Educational Needs to support them either in school or with alternative therapy and provision. These are the most vulnerable students who most need our support.

What this means for schools is that they are dipping into their own budgets and relying on community good will to meet the sometimes complex needs of their young people. The students in this category may need one to one support, a specific timetable or physical therapy in order to continue to access education. It is one of the most challenging, but most important and most rewarding areas of school life. Without the funding needed to provide this support, schools are drawing further on their budgets and reserves to offer this support which the students are entitled to, but not receiving from the government.

These are issues I simply don’t see the Conservatives, currently buying primary schools chess sets while their rooves fall down, talking about.

As a teacher, education is my number 1 priority. I think our government should be offering to:

- Fund schools properly.

It is easy to say that money is the answer to every question, but what it creates in schools is capacity. With more money, you can afford to adapt your site for students with physical disabilities; to employ more teaching and support staff to fill some of the gaps; and to work with students one on one to help them resettle into school life. This supports the most vulnerable students, be that behaviourally or in terms of additional needs.

There is an inefficiency in over-staffing, but there is also a benefit in building slack into the system, so that if one member of staff is away one day there are others there to take over. Schools are currently doing more and more on the shoulders of fewer and fewer people, which creates incredibly fragile systems. The funding to change this would go a long way.

- Invest in school facilities.

Even without the RAAC problem, many school buildings are dilapidated and no longer fit for purpose. Many of us will remember being taught in the “temporary” portacabin that had been there for 20 years: most of them are still there and are now called “classrooms”. The pandemic revealed how poorly ventilated many of our classrooms are, with narrow corridors and stuffy rooms, and the fact that some schools needed to close in our heatwave in July 2022 showed that our buildings are not resilient to the climate crisis.

You have one shot at education, and the environment you learn in should be fit for the modern day and be comfortable and feel safe.

Investing in schools is an investment in the future, and our government should be establishing a rebuilding project, to make our schools open, inclusive, modern spaces to learn in, built to high environmental standards.

- Analyse the impact of the pandemic and plan for the future.

It is undeniable that the pandemic has had a huge impact on our students. The rise in suspension levels, alongside the challenges of social media, and anti-social behaviour are all legacies of a sudden knee jerk change in structure. Our students were sent home one day, to be brought back the next and then sent home again. This has not been easy for their education, their mental health and their friendships.

The Covid-19 enquiry was announced in December 2021, to analyse the UK’s response to the pandemic. The scope of this enquiry rightly includes public health, health and care and the economy, but has no mention of education.

We do not know whether the decisions made to suddenly close schools for the long-term during the pandemic was the right thing to do or not. It may have had an impact on slowing down the spread of the virus, but this needs to be properly weighed up against the impact it had, and is still having, on young people’s mental health, learning, behaviour and social skills. If we are now living in an era where future pandemics are possible, we need to establish what the science shows about the impacts of closing schools, and find ways, guided by the science, to ensure the best decisions are made in future which takes on board these lessons.